Global Risks Report 2023

2. Global Risks 2033: Tomorrow’s Catastrophes

2.1 The world in 2033

As risks highlighted in the past chapter unfold today, much-needed attention and resources are being diverted from global risks that may become tomorrow’s shocks and crises. The Global Risks Perceptions Survey (GRPS) addresses a one-, two- and 10-year horizon. Chapter one addressed the present and two-year time frame, focusing on currently unfolding and shorter-term risks. This chapter focuses on the third time frame: risks that may have the most severe impact over the next 10 years.

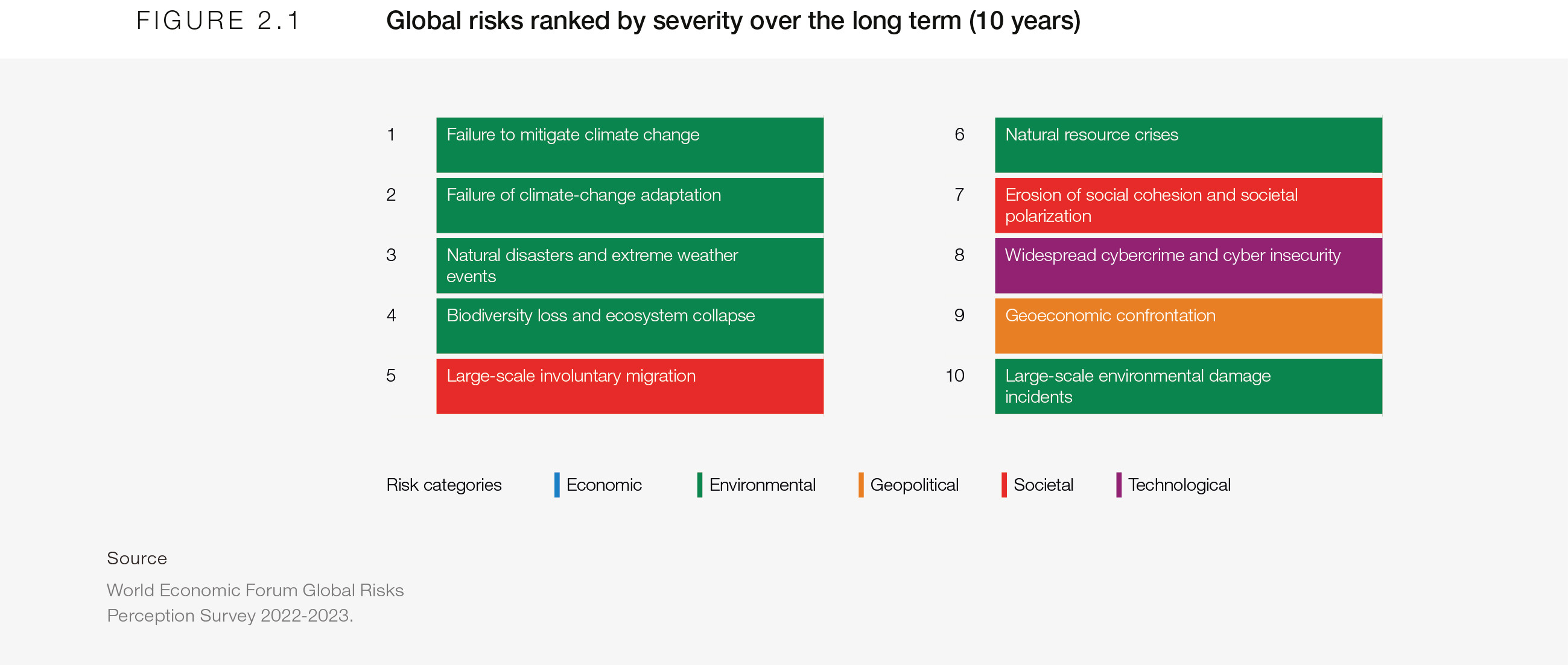

Based on GRPS results, the longer-term global risks landscape is also dominated by deteriorating environmental risks (Figure 2.1). More specifically, climate- and nature-related risks lead the top 10 risks, by severity, that are expected to manifest over the next decade. Differentiated as separate risks for the first time in the GRPS, Failure to mitigate climate change and Failure of climate-change adaptation top the rankings as the most severe risks on a global scale, followed by Natural disasters and extreme weather events and “Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse”.

Comparing the two-year and 10-year time frames provides a picture of areas of increasing, decreasing and continued concerns according to GRPS respondents (Figure 2.2). The top right of the graph indicates global risks that are perceived to be the most severe in both the short and long term. These are consistent areas of global concern and, arguably, attention. Four environmental risks have worsening scores over the course of the 10-year time frame, indicating respondents’ concerns about increased severity of these risks in the longer term. “Large-scale involuntary migration, rises to fifth place in the 10-year time frame, while Erosion of social cohesion and societal polarization is perceived to be slightly more severe over the longer term.

Risks that are growing in severity over the longer term include Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse and Misinformation and disinformation. Among other technological risks, as indicated in the far left of the graph, “Digital inequality and lack of access to digital services” and “Adverse outcomes of frontier technologies” are also anticipated to significantly deteriorate over the 10-year time frame.

The scores of multiple social risks are also worsening, including “Severe mental health deterioration”, “Collapse or lack of public infrastructure and services”, and “Chronic diseases and health conditions”. In contrast, economic risks such as Failure to stabilize price trajectories, A prolonged economic downturn, “Collapse of a systemically important industry or supply chain”, and “Asset bubble burst” are perceived to fall slightly in expected severity over the ten-year time frame.

The far right of the graph indicates that today’s most prominent risk, the Cost-of-living crisis, is anticipated to drop in severity over the longer term. Towards the center, the scores of geopolitical risks were mixed, with the “Use of weapons of mass destruction” remaining consistent, “State collapse or severe instability” and “Ineffectiveness of multilateral institutions” worsening and Interstate conflict perceived as decreasing in severity.

This year, we look at five newly emerging or rapidly accelerating risks clusters – drawn from the economic, environmental, societal, geopolitical and technological domains, respectively – that could become tomorrow’s crisis. We explore their current drivers and emerging implications, and briefly touch on opportunities to forestall and reshape these outcomes by acting today.

These include:

– Natural ecosystems: deteroriating risks to natural capital (“assets” such as water, forests and living organisms) due to growing trade-offs and feedback mechanisms relating to climate change, taking us past the point of no return.

– Human health: chronic risks that are being compounded by strained healthcare systems facing the social, economic and health aftereffects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

– Human security: a nascent reversal in demilitarization and growing vulnerability of nuclear-armed states to emerging technologies, emerging from new weapons and multi-domain conflicts.

– Digital rights: the potential evolution of data and cyber insecurity, given the slow-burning, insidious erosion of the digital autonomy of individuals, putting privacy in peril.

– Economic stability: growing debt crises, with repercussions for financial contagion as well as collapse of social services, emerging from a global reckoning on debt and leading to social distress.

The newly emerging or rapidly accelerating risk clusters identified this year are not intended to be exhaustive. Rather, they aim to provide topic-specific analysis, nudge pre-emptive action and attention, and serve as examples for applying similar analysis to a range of other future risk domains.

2.2 Natural ecosystems: past the point of no return

Biodiversity within and between ecosystems is already declining faster than at any other point during human history.1 Unlike other environmental risks, Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse was not seen as pressing of a concern by GRPS respondents over the short term. Yet it accelerates in perceived severity, rising to 4th place over the 10-year time frame (Figure 2.1).

Human interventions have negatively impacted a complex and delicately balanced global natural ecosystem, triggering a chain of reactions. Over the next 10 years, the interplay between biodiversity loss, pollution, natural resource consumption, climate change and socioeconomic drivers will make for a dangerous mix (Figure 2.3). Given that over half of the world’s economic output is estimated to be moderately to highly dependent on nature, the collapse of ecosystems will have far-reaching economic and societal consequences. These include increased occurrence of zoonotic diseases, a fall in crop yields and nutritional value, growing water stress exacerbating potentially violent conflict, loss of livelihoods dependent on food systems and nature-based services like pollination, and ever more dramatic floods, sea-level rises and erosion from the degradation of natural flood protection systems like water meadows and coastal mangroves.

Terrestrial and marine ecosystems are facing multiple pressure points due to their undervalued contribution to the global economy as well as overall planetary health. While not the sole drivers, at the heart of this potential catastrophe are key trade-offs and feedback mechanisms emerging from current crises. Without significant policy change or investments, the complex linkages between climate change mitigation, food insecurity and biodiversity degradation will accelerate ecosystem collapse.

Exponentially accelerating nature loss and climate change

Nature loss and climate change are intrinsically interlinked – a failure in one sphere will cascade into the other, and attaining net zero will require mitigatory measures for both levers.2 If we are unable to limit warming to 1.5°C or even 2°C, the continued impact of natural disasters, temperature and precipitation changes will become the dominant cause of biodiversity loss, in terms of composition and function (Figure 2.4).3 Heatwaves and droughts are already causing mass mortality events (a single hot day in 2014 killed more than 45,000 flying foxes in Australia), while sea level rises and heavy storms have caused the first extinctions of entire species.4 Arctic sea-ice, warm-water coral reefs and terrestrial ecosystems have been found most at risk in the near term, followed by forest, kelp and seagrass ecosystems.5

The impacts of climate change on ecosystems can further constrain their mitigation effects. Increased severity and frequency of extreme weather events and other natural disasters are already degrading nature-based solutions to climate change, such as wildfires in forests used for carbon offsetting.7 In addition, a variety of ecosystems are at risk of tipping over into self-perpetuating and irreversible change that will accelerate and compound the impacts of climate change. Continued damage to carbon sinks through deforestation and permafrost thaw, for example, and a decline in carbon storage productivity (soils and the ocean) may turn these ecosystems into “natural” sources of carbon and methane emissions.8 The impending collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets may contribute to sea-level rise and coastal flooding, while the “die-off” of low-latitude coral reefs, the nurseries of marine life, are sure to impact food supplies and broader marine ecosystems.

Trade-offs between food security and nature conservation

Land-use change remains the most prolific threat to nature, according to many experts.9 Agriculture and animal farming alone take up more than 35% of Earth's terrestrial surface and are the biggest direct drivers of wildlife decline globally. The ongoing crisis in the affordability and availability of food supplies positions efforts to conserve and restore terrestrial biodiversity at odds with domestic food security, as explored in Chapter 3: Resource Rivalries.

Conservation efforts and nature-based solutions (which can offer biodiversity co-benefits) will struggle to be commercially competitive with intensive, yield-focused agricultural practices, particularly in densely populated, agrarian nations. State incentives to boost local production and reduce reliance on imports – in a reaction to current geopolitical and supply pressures – could come at the cost of ecosystem preservation. Technology will provide partial solutions in the countries that can afford it. For example, the global vertical farming market has been predicted to grow at a compound annual rate of 26% and hit $34 billion by 2033.10 These agricultural production techniques increase food output per unit area with a smaller water and biodiversity footprint, but can actually be more carbon-intensive and may have an indirect land footprint that exceeds open-field farming in some regions.11

Given a highly uncertain economic outlook, developing and emerging markets may struggle to close the funding gap to increase agricultural productivity. Pressure on biodiversity will likely be further amplified by continued deforestation for agricultural processes, with an associated demand for additional cleared cropland,12 especially in subtropical and tropical areas with dense biodiversity such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.13 Biodiversity and ecosystem preservation could be supported through the expanded use of concessional financing and debt restructuring: 58 developing countries exposed to climate change have almost $500 billion in collective debt reservicing payments due in the next four years.14 Increased deployment of debt-for-nature swaps, for example, could be targeted towards conservation and restoration. In fact, this type of restructuring is being pursued by Ecuador, Sri Lanka and Cape Verde.15 However, these mechanisms could contribute to shorter term challenges of food insecurity, rising cost of living and declining government revenue.16 In addition, indigenous communities can be disproportionately at risk from these activities. “Fortress conservation” can encroach on indigenous land tenure and has previously been linked to forced evictions, even fatalities.17

Yet, there is a more existential feedback mechanism to consider: biodiversity contributes to the health and resilience of soil, plants and animals, and its decline puts both food production yields and nutritional value at risk.18 This could then fuel deforestation, increase food prices, threaten local livelihoods and contribute to diet-related diseases and mortality (explored in Chapter 2.3: Human health). It may also lead to Large-scale involuntary migration, a new entrant in the Top 10 rankings in the GRPS survey (Figure 2.1) and analysed in last year’s Global Risks Report chapter ‘Barriers to Migration’.

New battlefronts between ecosystems and “green” energy sources

The transition to clean energy is critical for the mitigation of climate change by reducing the carbon footprint of energy compared to fossil fuels. Yet the rapid expansion of green infrastructure in a quest for energy security may have unintended impacts on domestic and broader ecosystems, as the dependencies on and risks to natural ecosystems of these technologies are, presently, less well understood. Although renewable energy infrastructure can be “nature-positive” – for example, wind farms acting as a “safe haven” for the recovery of marine populations and the seabed – green sources of energy can also cause environmental degradation, such as habitat loss, sound and electromagnetic pollution, introduction of non-indigenous species and changes to animal migratory patterns.19

Renewable energy technologies are also reliant on non-renewable, abiotic natural capital (metals and minerals, as explored in Chapter 3: Resource Rivalries). These are sourced from the geosphere, which, together with the hydrosphere, provide the physical habitat for the global ecosystem. These resources are often concentrated in countries with poor governance of nascent, artisanal and illicit mining or less stringent environmental and social regulations – increasing the likelihood of more widespread destruction of nature and devastation of local communities and indigenous groups. Mining of rare earth elements in Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have already caused widespread deforestation, habitat destruction of endangered species and water pollution, and have been linked to human rights abuses and financing of militia groups.20 While offering the possibility of socioeconomic development and diversification, the expansion of green metals mining in nature-rich or ecologically sensitive areas, such as the Plurinational State of Bolivia and Greenland, has the potential to destabilize water tables and disrupt ecosystems.21 The pressure to push ahead with deep-sea mining also entails significant risks, due to the unknown impacts to critical oceanic ecosystems.22

It is clear that both the scale and pace needed to transition to a green economy require new technologies. However, some of these technologies risk impacting natural ecosystems in new ways, with limited opportunity to “field-test” results. The urgency of climate change mitigation is incentivizing the deployment of new technologies, potentially with less stringent testing and protocols. Carbon removal technologies will be particularly essential to achieve a net zero world if anthropogenic emissions do not sufficiently decline, or emissions from natural resources continue to increase. Gene editing to enhance natural carbon capture productivity, geo-engineering for carbon removal,23 and solar radiation management all pose major future risks – from enhanced water stress, nutrient “robbing” and redistribution of diseases to termination shock and the weaponization of stratospheric aerosol technologies.24 Unintended consequences relating to technological “edits” to the atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere and geosphere can occur at speed, raising the risk of accidental extinction events.

Acting today

Averting tipping points requires a combination of conservation efforts, interventions to transform the food system, accelerated and nature-positive climate mitigation strategies, and changes to consumption and production patterns. This involves realigning incentives and upgrading governance structures, fueled by better data and tools to capture the interdependencies of food, climate, energy and ecosystems.

There are already initial signs of shifts in this direction. The increasing visibility and influence of multilateral and market-led initiatives, such as the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TFND) set to launch later this year, are positive developments. The 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD COP15) resulted in the Montreal-Kunming agreement, setting out new global targets for 2030 such as reforming environmentally damaging subsidy systems and restoring 30% of the planet’s degraded ecosystems. These significant steps confirm that the global community recognizes that the risks associated with nature loss, food production, energy generation and climate change cannot be fully mitigated in isolation. However, the translation into public- and private-sector action remains to be seen, particularly given limited progress on previous biodiversity – and climate –targets to date.

Although the relationship between climate and nature heightens the likelihood of a series of escalating and potentially irreversible feedback loops, it can equally be leveraged to broaden the impact of risk mitigation activities. Given increasing financial and capacity trade-offs, investment in resilience must focus on solutions that build preparedness for multiple risks. By restoring biodiversity in soils, for example, regenerative agriculture has the potential to store large amounts of carbon.

A focus on biodiversity preservation should drive and prioritize local adaptation and community resilience – and in doing so, contribute to the mitigation of climate change globally. Altered land management practices like afforestation, micro-irrigation and agroforestry are a low-cost way to increase resilience to extreme weather. The protection and restoration of marine biodiversity, such as mangrove systems, can enhance rather than compete with domestic food web productivity and security. It can also support local industries and livelihoods and provide protection from extreme weather. Such activities also produce co-benefits at a global level, such as enhancing carbon sequestration and climate regulation, offering potential revenue streams for developing nations in the form of carbon credits. Similarly, scaling up practices such as biocultural preservation, indigenous community management and integration of traditional knowledge into food production and cultivation can provide dual socioeconomic and environmental benefits.25

2.3 Human health: perma-pandemics and chronic capacity challenges

Global public health is under growing pressure and health systems around the world are at risk of becoming unfit for purpose. The COVID-19 pandemic further amplified ever-present spectres and emerging risks to physical and mental health, including antimicrobial resistance (AMR), vaccine hesitancy and climate-driven nutritional and infectious diseases (described in ‘False Positive: Health Systems under New Pressures’ in our 2020 edition, published before the pandemic took hold). Given current crises, mental health may also be exacerbated by increasing stressors such as violence, poverty and loneliness.

There is also a rising risk of a “panic-neglect” cycle. As COVID-19 recedes from the headlines, complacency appears to be setting in on preparing for future pandemics and other global health threats. Healthcare systems face worker burnout and continued shortages at a time when fiscal consolidation risks deflecting attention and resources elsewhere. More frequent and widespread infectious disease outbreaks amidst a background of chronic diseases over the next decade risks pushing exhausted healthcare systems to the brink of failure around the world.26

Pandemic aftershocks meet silent health crises

Global health outcomes have been weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic, with lingering effects. Early evidence points to a post-COVID-19 condition impacting the quality of life and occupational status of individuals – contributing to work absences and early retirements, tighter labour markets and a decline in economic productivity. The resulting economic hit is estimated to be from roughly $140-600 billion to up to $3.7 trillion in the United States of America, and close to AUD$5 billion per year in Australia if current costs persist, reflecting loss of quality of life, lost earnings and output, and higher spending on medical care.27 The pandemic also diverted resources from other diseases such as cancer screening and tuberculosis,28 and immunization campaigns were put on hold. Vaccination rates for polio fell to the lowest level in 14 years, perhaps ushering in the return of the wild strain to Africa in 2021.29

Beyond the lingering impact of COVID-19, the potential stresses imposed by climate change and nature loss on health are likely to grow, ranging from air pollution and heightened exposure to wet heatwave days (which increase heat stress on humans), to disrupted access to safe water and sanitation and increases in waterborne diseases due to floods. Urbanization, land use change and nature loss are heightening the emergence and re-emergence of diseases, including invasive fungal diseases, while global warming is increasing the number of months suitable for transmission of existing diseases such as malaria and dengue fever.30 Climate change is also expected to exacerbate malnutrition as food insecurity grows. Increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can result in nutrient deficiencies in plants, and even accelerated uptake of heavy minerals, which have been linked to cancer, diabetes, heart disease and impaired growth.31

Expanding sources of disease will combine with persistent disease burdens to entrench a growing health burden in developing and advanced economies alike. There has been a noticeable shift towards non-communicable diseases over the past decade (Figure 2.5), linked to population growth and ageing alongside lagging coverage by health systems. A key implication is the resulting loss of functional health and rise in disabilities, rather than deaths. Medical advances have made it possible for people to live with multiple co-morbidities (such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and depression), but these remain complex and expensive to manage. People are living more years in poor health, and we may soon face a more sustained reversal in life expectancy gains beyond the influence of the pandemic.

Notably, although some disease burdens are growing, all health-related risks fell into roughly the bottom third of the GRPS’ global risk rankings over both the two- and 10-year period (Figure 2.2). “Infectious diseases” plummeted in risk perceptions, from the sixth-most severe risk on a global scale over the next 10 years in last year’s Global Risks Report, to 27th place this year. Further, female respondents to the GRPS consistently assessed health-related risks as more severe than their male counterparts. Chronic diseases and health conditions and Severe mental health deterioration were ranked 13th and 14th by female respondents, with the related Collapse or lack of public infrastructure and services in 19th place, compared to rankings of 23rd, 28th and 27th, respectively, by male respondents.

The decline in risk perception is likely driven by pandemic fatigue and the human tendency to focus on fresh, recent and more visible crises. Yet “silent” crises with cumulative impacts can quickly outpace a one-off, catastrophic event. The COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to nearly 6.6 million deaths globally at the time of writing, noting that this figure will likely increase with China’s lifting of stringent COVID-19 restrictions after three years.33 In comparison, an estimated 4.95 million deaths were associated with drug-resistant bacteria (AMR) in 2019 alone, with roughly 1.27 million of these considered directly attributable to AMR.34 Air pollution was estimated to be responsible for a further 9 million deaths in the same year, corresponding to one in six deaths worldwide.35 While there are limitations to the collection and analysis of data in all three cases, and COVID-19’s outcomes may have been far worse in the absence of rapid action, the comparisons highlight the potential of silent crises to create compounding, runaway damage.

Chronic capacity challenges

As disease burden grows and innovation widens the scope of what medicine can treat, inexorable demand for healthcare is running up against chronic capacity challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the delivery of prevention and treatment services, resulting in a backlog for hospital and community care that may prove challenging to clear. More than 7 million people in the United Kingdom of Great Britain (more than one-tenth of the population) were waiting for non-emergency medical care in September 2022, while 10% of job posts remained vacant as the National Health Service struggled to retain staff.36

Health systems are likely to face intensifying financial pressure – with budget cuts or revenue loss as well as higher costs of goods and labour – as inflation persists, economies grow slowly or stagnate, and governments reprioritize expenditure to address more salient social and security concerns. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated staff shortages, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted a global shortfall of 15 million health workers by 2030.37 Some health systems are seeing productivity decline as experienced employees leave due to exhaustion, burnout and concerns about staff and patient safety. Skills and infrastructure gaps undermine capacity further as staff become overwhelmed by challenges for which they are not adequately equipped or supported to solve, leading to more strikes over pay and staffing levels.

Medical inflation is expected to continue to outstrip GDP growth in many countries,38 and financial pressures on working populations will intensify as dependency ratios rise. The United States of America already spends nearly 20% of its GDP on healthcare, even before its largest population cohort (the “Baby Boomers”) has retired.39 Governments, insurers or employers may respond by limiting coverage and shifting a greater proportion of the costs to individuals, reducing access and affordability of healthcare. Two-tier health systems, already prevalent in many advanced and developing economies, may become further entrenched, with a profitable private sector catering to patients with greater ability and willingness to pay, while poorer people remain reliant on increasingly threadbare public provision.40

A persistent mismatch between demand and supply gradually weakens the ability of health systems even in richer countries to cope and adapt, eroding care quality and shrinking healthcare access. Fragile health systems could quickly become overwhelmed by one or more catastrophic events. A large-scale cyberattack, war, extreme weather event or new or re-emergent infectious diseases could trigger health system collapse within one or more regions, resulting in a sudden surge of deaths from all causes. More gradual deterioration of health systems would also weaken overall health, widen health disparities, slow economic activity and undermine political and societal stability as a safety net disintegrates.

Socioeconomic syndemics

Combined with fragile health systems, there is a risk of a rise in “syndemics”: a set of concurrent, mutually enhancing health problems that impact the overall health status of a population, within the context of political, structural or social environments.41 The concept has long been applied to HIV research. More recently, it has been considered in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and chronic disease burdens, which have resulted in higher morbidity and mortality rates among socially disadvantaged communities.42 A similar pattern could now play out at a systemic level: deteriorating social, economic and political contexts will contribute to endemic diseases and lead to poorer health outcomes for select communities.

Inequality and conflicts in societal values could precipitate regulatory changes regarding education, employment, housing, gender, immigration and the environment, some of which could have unintended compounding effects on specific diseases. For example, a lack of LGBTQ protection has been linked to poorer health outcomes relating to HIV, due to the resulting avoidance of healthcare.43 Current crises might further derail health outcomes and equity. Chronic financial stress and rationing of essentials – such as having to choose between heating and eating – will have long-term physical and psychological impacts even on healthy people.44 Lower confidence in public institutions has already resulted in less effective pandemic responses, and growing misinformation and disinformation could further increase vaccine hesitancy, which has already led to the re-emergence of locally-eradicated diseases such as polio.45 These patterns may be reinforced as there is a clear rise in the erosion of social cohesion (see Chapter 1.2: Societal polarisation).

Geopolitical tensions could limit the co-development and sharing of new scientific breakthroughs, limiting respective abilities to address ever-present risks such as AMR as well as new ones. Export restrictions applied to medicine and medical products could cause a humanitarian crisis and spiral into controls over even more existential resources – most notably food – with compounding effects on health. Disparities in healthcare access may also worsen across and within countries as a result of economic inequality. For example, while advances such as in personalized, genomic and proteomic medicine can vastly improve health outcomes for chronic and degenerative conditions, they come with hefty price tags that may constrain widespread use; gene therapies can cost upwards of $2 million.46 A rise in state instability and conflict would further limit the delivery of aid, disrupt vaccination programmes and put health workers at risk. This was evident in the case of polio vaccination workers killed in Afghanistan last year.47

Acting today

It is essential that we embed hard-earned lessons in preparedness for the next iteration of health crises. A continued focus on public health policy and interventions can have outsized impacts at national and regional levels, as a great deal of chronic disease burden is, in fact, preventable.48 Realizing public health gains will require governments and business to promote the conditions that underpin wellbeing and encourage healthy lifestyles, such as good food, clean air, secure housing and social cohesion.

Public health agencies, healthcare providers and funders can play a key role by improving interactions and coordination between different parts of the health system to share information, expand capacity and improve overall population health. Planning for the long run will help governments better assess and manage health system risks, as will aligning policies that directly or indirectly affect health (such as agricultural policies that drive antibiotic use and increase AMR risk). Governments and businesses will also need to add a health dimension to crisis preparedness plans to withstand emerging risks.

In parallel, national and global health institutions and systems need to be strengthened in the face of multiple challenges. Innovation in care delivery, staffing and funding models are required for health systems to provide disease prevention, early detection and complex care cost-effectively for an increasingly frail and chronically ill population. There is also potential for healthcare to reap the advantages of technological advances and digital transformation that other sectors have embraced, such as augmenting capacity with technology and combining virtual and in-person care to reduce costs.

Opportunities to strengthen public health exist across countries, too, especially in the areas of pandemic surveillance and preparedness, scientific collaboration, and in mitigating global threat drivers such as climate change and AMR. It is essential that health nationalism is avoided in the face of the geopolitical and security considerations already underway today. Continued collaboration and information flows in the field of healthcare, pharmaceuticals and life sciences underpin efforts to ensure that our understanding and capability can continue to effectively address emerging health risks.

2.4 Human security: new weapons, new conflicts

GRPS results suggest that economic and information warfare will continue to pose a more severe threat than hot conflict over the next decade. Interstate conflict and Use of weapons of mass destruction were ranked lower in anticipated severity compared to “Geoeconomic confrontation” and Misinformation and disinformation over the 10-year time frame (Figure 2.2).

Past decades were defined by the non-deployment of humanity’s most powerful weapons and no direct clashes between global powers. Prior to 2022, militarization had fallen in all regions, with recent data showing an overall decline in nearly 70% of the countries covered by the Global Peace Index 2022 over the past 15 years.49 Even between 2021 and 2022, the holdings of nuclear and heavy weapons, military expenditure, weapons imports and armed services personnel rates declined (Figure 2.6). Yet the world still became less peaceful, with more violent demonstrations, external conflict and intense internal conflicts during the same fifteen-year period.50

A reversal of the trend towards demilitarization will heighten the risk of conflict, on a potentially more destructive scale. Growing mistrust and suspicion between global and regional powers has already led to the reprioritization of military expenditure and stagnation of non-proliferation mechanisms. The diffusion of economic, technological and, therefore, military power to multiple countries and actors is driving the latest iteration of a global arms race. Unlike previous power dynamics that were shaped by weapons of deterrence, the next decade could be defined by devastation from precision attacks and expanded conflicts.

New military architects and architecture

The 2010s saw global military expenditure growing in line with GDP and government budgets (5% of expenditure, down from 12% in the early 1990s).51 However, today, global military expenditure as proportion of GDP is rising, driven predominantly by higher spending by the United States of America, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Russia, India, China and Saudi Arabia. Japan announced a proposal to double its defence budget to $105 billion (2% of its GDP) in May last year, and Qatar has increased spending by 434% since 2010 in response to blockades.52 The war in Ukraine – as well as lukewarm condemnation by a few key geopolitical players – has driven recent pledges by NATO members to meet or exceed the target of 2% of GDP, which, if met by all members, would represent an increase in total budget by 7% in real terms.53 Widespread defence spending, particularly on research and development, could deepen insecurity and promote a race between global and regional powers towards more advanced weaponry.54

The private sector is set to increasingly drive the development of military technologies, yielding advancements in semiconductor manufacturing, AI, quantum computing, biotechnology and even nuclear fusion, among other technologies.55 Many of these are general purpose in nature with civilian applications, but are also a force multiplier of military power, enhancing the capabilities of autonomous weapons, cyberwarfare and defensive capabilities. Emerging technologies will be increasingly subject to state-imposed limits to cross-border flows of talent, IP, data and underlying technologies (such as extreme ultraviolet lithography equipment) and resources (such as critical metals and minerals), to constrain the comparative rise of foreign rivals. Enhanced focus and investment will drive innovations – global research and development expenditure hit 2.63% in 2021, the highest in decades.56 There are sure to be multiple architects (Figure 2.7), with parallel innovations and interoperable ecosystems that will not only undermine efficiencies and duplicate efforts – even prior to the tightening of market conditions, technological fragmentation was estimated to result in losses of up to 5% GDP for many economies57 – but may also increase risk.

Military-driven innovations in relevant fields will have knock-on benefits for economic productivity and societal resilience, including personalized and preventative medicine, climate modelling and material science development. The influence of blocs will grow, closely tying together alliances across security, investment, trade, innovation, talent and standards. For example, Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand were recently invited to participate at a NATO summit for the first time.59 As developing economies seek to enhance their security in the new military architecture, they will be pulled deeper into the wider economic and military expansion of larger powers.60 However, the Global South also risks being priced out of security and broader technological advancements. For example, the diffusion of dual-use technologies may be constrained or subject to high royalties, widening global inequality.

Next-generation technologies and multi-domain conflicts

New technologies will change the nature of the threat to national and international security, with a rise in multi-domain conflicts that blur the definition of conventional warfare. “Future battlefields” and methods of confrontation are expanding, encompassing the land, sea, air, cyberspace and outer space (explored in the Crowding and Competition in Space Chapter in last year’s Global Risks Report).61 Anti-satellite and hypersonic weapon capabilities have already been demonstrated by some states.62 Directed Energy Weapons are expected to make significant progress over the next decade, with the potential to disable satellites, electronics, communications and positioning systems, and some of these weapons may be more cost-effective than traditional munitions.63 Quantum computing may be harnessed to identify new materials for use in stealth technologies, and cyber and information warfare will be deployed to target vulnerabilities in increasingly sophisticated military technologies, which could range from disinformation campaigns to hacking hardware in nuclear defence systems.64

Importantly, these technologies are emerging in parallel – with the potential for simultaneous and compounding impacts on global security.65 The testing and demonstration of enhanced capabilities could destabilize geopolitical relationships and accelerate an arms race, even in the absence of triggering conventional or nuclear strikes. This race will also slow the development of and adherence to norms, standards and safety protocols governing the development and use of these technologies, leaving fundamental questions unanswered – such as how to pursue fields like quantum computing, without simultaneously destabilizing the world’s encryption systems and accelerating a global arms race.66 As a result, self-regulation by the private sector will likely rise, as will consumer campaigning against military applications of technologies, such as the “Stop Killer Robots” coalition.

While social and global norms constraining the use of nuclear weaponry remain high, the unconstrained pursuit of lower-yield weaponry and stronger defensive military technologies could undermine the perceived security provided by nuclear weapons, putting in jeopardy a delicate strategic balance. Emerging technologies heighten the actual or perceived vulnerability of countries to attack, including nuclear-armed ones.67 Advanced sensing technologies, particularly once enabled by quantum computing, could theoretically expose second-strike capabilities (mobile nuclear weapons) to real-time targeting and elimination.68 The potential for lower-yield, more targeted nuclear weaponry has already brought into question the viability of the current threshold of activation for the “nuclear umbrella” of the United States of America, while an escalating arms race may cause countries to roll back the no-first-use principle to enhance deterrence.

Together, these new technologies are escalating rhetoric and the pressure on existing governance mechanisms. This could lead to an increase in the global inventory of nuclear warheads for the first time since the Cold War,69 raising the risk of accidental, miscalculated or deliberate clashes, with devastating results. Nuclear-armed countries continue to modernize arsenals and develop new types of delivery systems; late last year, the United States of America unveiled its first new nuclear-capable strategic bomber in more than three decades. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which entered into force in early 2021, continues to be opposed by all nine declared nuclear-armed states.70 North Korea conducted the largest number of annual ballistic missiles launches last year, and there is escalating rhetoric in the context of the war in Ukraine.71 The possibility of nuclear-sharing arrangements or even potential acquisition in limited circumstances has been raised in some non-nuclear states, such as Japan and the South Korea.72 Negotiations on the revival of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) have also stalled.73 Although both the United States of America and Russia have continued to adhere to the New START Treaty, and disarmament technically continues, the usable military stockpiles of both countries – accounting for 90% of all nuclear weapons – remained stable in 2021.74

A rise in rogue actors

Proliferation of more destructive and new-tech military weaponry may enable newer forms of asymmetric warfare, allowing smaller powers and individuals to have a greater impact at a national and global level. Financial, information and intelligence thresholds are lower in many dual-use technologies. For example, advances in biotechnologies could enable the creation of pathogens by small groups or even individuals.75 Low-cost drones utilizing swarm intelligence can be used to attack high-value units, including bases and fuel tanks.76 The most recent available data suggests a consolidation of arms exports, with North America and Europe accounting for 87% of all arms exports from 2017-2021, alongside an accompanying decline from China and Russia.77 However, any future diffusion of market share will increase the likelihood of advanced military systems being shared with more adversaries, across a broader geographic area.78

The lower cost and potential spread of conventional or chemical, biological, or nuclear weaponry to rogue actors will further erode the government’s “monopoly on violence”. This can increase the vulnerability of states and fuel migration, corruption and violence that can spill over borders.79 Drones have already been used by non-state actors in Syria, Libya and Yemen, and both military and civilian drones have been used by formal security forces, paramilitary groups and non-combatants in Ukraine.80 Despite limited transparency and accountability, there has also been a growing reliance on private militia and security services to protect assets and infrastructure, including vessels, commercial shipping, offshore platforms and ports. The use of these proxy, hybrid and private armies in multiple security contexts has been linked to violations of human rights and international law in conflict, post-conflict and peacetime settings.81

The distinction between civilian and military spheres is blurring further: these technologies expose populations to direct domestic threats, often with the objective of shattering societal functioning. This includes the physical and virtual disruption of critical resources and services at both a local and national level, such as agriculture and water, financial systems, public security, transport, energy, and domestic, space-based and undersea communication infrastructure. “Breakdown of critical information infrastructure” was ranked tied 16th by GRPS respondents in terms of perceived severity over the next 10 years, but its relationship with Interstate conflict was not highlighted (Figure 2.8). Concerted attempts at cyberattacks against Ukraine were made last year, including against communication services, financial websites and electricity grids. Data theft and deep-fake technology also sought to prevent access to services, targeting flows of refugees, medicines, food and relief supplies.82 The critical functioning of whole economies will only become more exposed with breakthroughs in dual-use technologies, most notably quantum computing.

Acting today

An international environment that is at greater risk of conflict and the less transparent attribution of unconventional engagement may weaken the shared moral, reputational and political costs that partially act as a deterrent to the deployment of destructive weaponry, including nuclear engagement. Undoubtedly, the strengthening of arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation agreements and norms, covering both existing and newer forms of military technologies, are essential to provide transparency. This can also reduce the risk of unintended escalation, for example by limiting the spillover of conflicts across domains, such as a cyberattack on critical infrastructure escalating into a targeted destructive exchange with lethal autonomous weapons.83 Establishing norms will be essential to ensuring the right balance is struck so that technological innovation can continue to be harnessed to improve socioeconomic outcomes for humanity.

However, achieving effective arms control will be even more challenging than in the past. It will require engagement with a broader range of actors – including academic researchers and the private sector – given the dual-usages of many of these technologies. Developments are quickly outpacing global governance processes. An escalating arms race will further hinder collaboration, but the regulation of new weapons technologies to control proliferation and usage can only be achieved through transnational cooperation. The first step should include greater recognition by global powers of the strategically beneficial value to agreements on key arms control issues. In the longer term, new strategies for global governance that can adapt to this new security context must be explored to assuage the concerns of nations and avoid a spiral of instability and accidental or intentional destruction.

2.5 Digital rights

Digital tools - increasingly sophisticated AI applications, interoperable edge computing and Internet of Things (IOT) devices, autonomous technologies – underpin the functioning of cities and critical infrastructure today and will play a key role in developing resilient solutions for tomorrow’s crises. Yet these developments also give rise to new challenges for states trying to manage the existing physical world and this rapidly expanding digital domain.

Based on GRPS results, “Widespread cybercrime and cyber insecurity” is a new entrant into the top 10 rankings of the most severe risks over the next decade. As highlighted in last year’s Global Risks Report chapter ‘Digital Dependencies and Cyber Vulnerabilities’, malicious activity in cyberspace is growing, with more aggressive and sophisticated attacks taking advantage of more widespread exposure. It was seen as a persistent threat by GRPS respondents as well as a strong driver of other risks (Figure 2.9).

The proliferation of data-collecting devices and data-dependent AI technologies could open pathways to new forms of control over individual autonomy. Individuals are increasingly exposed to the misuse of personal data by the public and private sector alike, ranging from discrimination of vulnerable populations and social control to potentially bioweaponry.84

Not all threats to the digital autonomy and sovereignty of individuals are malicious in nature. Larger data sets and more sophisticated analysis also heighten the risk of the misuse of personal information through legitimate legal mechanisms, weakening the human right to privacy,85 even in democratic and strongly regulated regimes. Legal incursions on privacy can be motivated by public safety considerations, crime prevention and response, economic development and better health outcomes. The privacy of personal and sensitive data is coming under increasing pressure by national security concerns, combining the protection of societies and states and the desire to gain a competitive technological and economic advantage.

Commercialized privacy

The right to privacy as it applies to information about individuals incorporates two key elements: the right not to be observed and the right to control the flow of information when observed.86 As more data is collected and the power of emerging technologies increases over the next decade, individuals will be targeted and monitored by the public and private sector to an unprecedented degree, often without adequate anonymity or consent.87

Surveillance technologies are becoming increasingly sophisticated through new technologies and techniques for gathering and analyzing data. The oft-cited examples are biometric identification technologies. In recognition of the potential risks posed to privacy and the freedom of movement, some companies have self-regulated the sale of facial recognition to law enforcement, and the use of this technology in public spaces faces an upcoming ban in the EU.88 Concerns also extend to the use of biometric technologies to analyze emotions. Other forms of monitoring are already becoming commonplace. Automated AI-based tools such as chatbots collect a wide amount of personal data to function effectively. The mass move to home working during the pandemic has led to tracking of workers through cameras, keystroke monitoring, productivity software and audio recordings – practices which are permitted under data-protection legislation in certain circumstances, but which collect deeper and more sensitive data than previous mechanisms.89

More insidiously, the spread of networked data is increasing surveillance potential by a growing number of both public- and private-sector actors, despite stringent regulatory protection.90 As our lives become increasingly digitalized over the next decade, our “everyday experience” will be recorded and commodified through internet-enabled devices, more intelligent infrastructure and “smart” cities – a passive, pervasive and persistent form of networked observations that are already being used to create targeted profiles.91 This pattern will only be enhanced by the metaverse, which could collect and track even more sensitive data, including facial expressions, gait, vital signs, brainwave patterns and vocal inflections.92

Individuals have usually consented to the collection of data for the associated beneficial use of the service or product, given the wave of new and stronger data protection policies in many markets.93 However, as the collection, commercialization and sharing of data grows, consent in one area may reveal far more than intended when aggregated with other data points. This is known as the “mosaic effect”, which gives rise to two key privacy risks: re-identification and attribute disclosure.94 Research suggests that 99.98% of US residents could be correctly re-identified in any data set – including those that are heavily sampled and anonymized – using 15 demographic attributes.95 Researchers have used this theory to uncover the political preferences of streaming users,96 match DNA from publicly-available research databases to randomly selected individuals,97 and link medical billing records from an open data set to individual patients.98

In consequential terms, this means that an international organization may share anonymized data with partner governments to support effective and efficient crisis responses. However, when combined with other data sets, it could allow the identification and tracking of vulnerable refugees and displaced persons – or compromise the location of camps and the supply chains of critical goods.99 Data on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and immigration status can be legally obtained in some markets and re-identified to varying degrees, enabling civil harassment and abuse. In one such example, the sexual orientation of a priest was obtained through the purchase of smartphone location data and announced by a religious publication.100

Data-enabled anocracies

The right to privacy is not absolute; it is traded-off against government surveillance and preventative policing for the purposes of national security. However, the surveillance potential of data has meant that access to sensitive information can increasingly be obtained without due process or transparency.101 In some cases, data protection laws that require consent effectively waive the legal protections against electronic surveillance of private communications and location data.102

In the United States of America, data is aggregated and sold on the open market with limited regulatory restrictions, meaning enforcement agencies can purchase GPS location data without warrants or public disclosure. For example, theoretically, police could use automated licence plate data (obtained by both private- and public-sector organizations) to prosecute out-of-state abortions – leading Google to announce that it would auto-delete location data for users that visit related centres.103 There is also increasing political and regulatory pressure to weaken encryption mechanisms adopted by private companies, particularly as it relates to terrorist investigations, despite broader implications to the ongoing security of civilians’ data.104

Potential for misuse will be especially problematic for users residing in countries with poor digital rights records, inadequate regulatory protection frameworks, or authoritarian tendencies. Forms of digital repression to quell politically motivated uprisings, such as the use of spyware to track activist activities, are already driving significant human rights violations in the Middle East.105 Recent reports have also highlighted potential digital rights violations in Africa stemming from the rapid expansion of biometric programmes that include voter registration, CCTV with facial recognition, mandatory SIM card registration and refugee registration.106 As more emerging markets look towards progressing their smart city plans, the collection of sensitive citizen data could expose societies to additional peril if poorly governed and protected.107

Security concerns posed by sensitive data and its potential abuse are well-recognized by governments. Countries have adopted more widespread data localization policies, tightened regulation of research collaborations, and banned some foreign-owned companies from certain markets, including telecommunications, surveillance equipment and mobile applications, to limit the collection and possession of sensitive data by non-allied states.108 Yet, less attention is being paid to the potential for overreach and abuse of this data in the name of national security. The slow and legal erosion of the digital sovereignty of individuals can have unintended and far-reaching consequences for social control and the erosion of democracies – including, for example, by compromising freedom of the press.

Growing trade-offs between innovation and security

Data is an important factor of production, and collection and flows are essential to fuel innovation for enhanced economic productivity (including automation), as well as socially beneficial uses.109 More expansive and innovative applications of AI and other emerging technologies will require cross-industry and public-private data aggregation. The centralization and consolidation of some types of data can lend a competitive advantage to economies, such as through improved health outcomes associated with advances in biotechnology.110 Yet governments may also increasingly struggle to balance the potential harm of privacy loss against the benefits of more rapid development of emerging technologies.

At the same time, to address the growing concentration of data in the hands of a small number of private-sector companies, governments may increasingly push for open-data policies from both public- and private-sector sources, mirroring recent regulatory moves by the EU around data spaces and marketplaces.111 Such policies – like the creation of public data trusts for research purposes – will likely affect both domestic companies and industries, as well as allied countries. This may benefit more widespread and diffused innovation, but it will also expand risks as they enable privacy breaches at a much larger scale. Privacy will strongly influence these agreements: the US government recently committed to heightened safeguards for transatlantic data flows, including from US intelligence activities.112

However, many of these data sets may still be subject to the threat of re-identification, even with recent developments in privacy-enhancing technologies such as synthetic data, federated learning and differential privacy.113 Research suggests that sensitive databases and technologies, such as pools of biological data and DNA sequencing, are already vulnerable to attack.114 Sensitive health data is governed inconsistently and the creation of large pools of personal data are creating lucrative targets for cybercriminals, particularly given the less stable geopolitical environment and limited norms currently governing cyberwarfare. The potential consequences of the large-scale theft of biometric or genomic information are largely unknown but may allow for targeted bioweaponry.

Acting today

At a national level, a patchwork of fragmented data policy regimes at local or state levels raises the risk of accidental and intentional abuses of data in a manner that was not considered by the individual’s original consent. Harmonizing policies at a national level will enable more effective, less complicated cross-border data-sharing mechanisms to power innovation while still ensuring adequate protection for individuals.

Developing a more globally consistent taxonomy, data standards, and legal definition of personal and sensitive information is a key enabler. These frameworks should recognize that sensitivity can arise from data-driven inferences that are enabled by large data sets, the proliferation of online social networks, and the blurring of personal and industrial data in the roll-out of the Internet of Things and implementation of “smarter” cities.115 For example, one company was recently fined under the EU’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) for targeted advertising that inferred a medical condition (deemed as a special category of data) on the basis of purchase history.116

Historically severe fines for data loss are also helping change the cost-benefit assessment around investment in cybersecurity measures, but questions remain around the individual rights to action, damage and compensation in cases of breach.117 It will be incumbent on organizations to consider the ethics of data collection and usage to minimize reputational considerations beyond regulatory compliance. In addition, spurred by both increased cyberattacks and tighter data laws, the voluntary disposal and destruction of personal data may become a stronger priority – with potential environmental co-benefits of minimizing data storage needs. Finally, governments will also need to development emergency capabilities to respond to data breaches and violation of privacy to minimize follow-on repercussions.

2.6 Economic stability: global debt distress

The threat of a sovereign debt crisis has been brewing, with public debt growing as interest rates have fallen. Governments have leveraged cheap money to invest in future growth and help stabilize distressed financial systems, providing massive fiscal support during the pandemic and to shield households and businesses from the current cost-of-living crisis. However, high levels of debt may not be sustainable under tighter economic conditions. The rapid and widespread normalization of monetary policies, accompanied by a stronger US dollar and weaker risk sentiment, has already increased debt vulnerabilities that are likely to remain heightened for years.

Stagflation on a global scale, combined with historically high levels of public debt, could have vast consequences.118 Even with a softer landing, the consequences of debt-trap diplomacy and rockier restructuring raise the risk of debt distress – and even default – spreading to more systemically important markets, paralysing the global economic system. Further, even comparatively orderly fiscal consolidation is likely to impact spending on human capital and development, ultimately threatening the resilience of economies and societies in the face of the next global shock, whatever form it might take.

The rising price of debt

General government gross debt in advanced economies hit 112% of GDP in 2022, compared to roughly 65% of GDP for emerging and developing markets.119 Yet as identified in Chapter 1.2, Economic downturn, some developing and emerging markets are feeling the impacts of tightening monetary policy and deteriorating economic conditions first and most acutely. For example, Ghana recently reached an agreement with the IMF regarding a $3 billion bailout and Zambia is seeking to conclude restructuring of $15 billion in external debt early this year. A broad-based global recession within the year120 could temper inflation and cap interest rate rises, but there is a higher risk of balance-of-payments crisis in the short-term, alongside a credit crunch over the mid to longer term.121 Emerging market banks also hold a larger proportion of domestic public debt, with the potential for distress to spread to banks, households and pension funds.122 Larger emerging markets exhibiting a heightened risk of default include Argentina, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Tunisia, Pakistan and Türkiye.123

Downside risks loom large, and another global shock could result in deeper and more prolonged economic disorder. Stagflation remains a severe risk for many economies. Current crises, such as the war in Ukraine and lingering impacts of COVID-19, are still impacting basic inputs, including labour, energy and food. Continued tightness in major labour markets may exacerbate wage inflation – meaning there may need to be a material increase in unemployment to contain consumer inflation. Extended supply-driven inflation could drive more painful interest rate rises, even amidst a slowdown in growth, leading to a harder landing and more widespread debt distress. A more systemically important emerging and developing economy – the likes of Mexico, South Africa and Poland – could face distress in coming years, raising the risk of financial contagion.124

As cautioned by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), miscalibration between fiscal and monetary policies could exacerbate this further, and in unexpected markets.125 Questions around the independence of central banks risk de-anchoring market expectations, and monetary intervention to counteract inflationary fiscal policies will only heighten the risk of longer economic malaise. The United Kingdom of Great Britain’s near-crisis in September last year is an example of the potential instability that could arise. The interest payable on the country’s public debt is expected to hit £120.4 billion for the financial year ending March 2023, up from £69.9 billion, the highest on record.126 The Bank of England raised rates from 0.1% in December 2021 to 3.5% in December 2022, yet was forced to intervene with an emergency quantitative easing programme in September to counter the market reaction to the UK government’s proposed fiscal stimulus.127 In the absence of a global shock, the “veto power” of the markets will increasingly limit fiscal expansion, even in advanced economies.128

The new geopolitics of debt

For now, the ratio of defaulted versus total global public debt remains very low by historic standards and far lower than peaks experienced in the 1980s (Figure 1.6). However, this partially reflects the growth in absolute public debt levels. Despite record IMF emergency lending and a $650 billion allocation in special drawing rights,129 more than 54 countries are currently in need of debt relief, representing less than 3% of the global economy. Yet these countries represent 18% of the global population and account for more than 50% of people living in extreme poverty.130 Fears of contagion and further capital flight could weaken debt sustainability in a growing number of lower-income countries. The scale of debt defaults will influence the depth of available restructuring, with some creditor countries hesitant to bail out distressed states on sufficiently concessionary terms, due to their own tightening fiscal space and rising domestic needs. There may also be a shift away from overseas development assistance towards loans to continue to support development and wield economic power. This has a lower domestic cost but exacerbates the debt burden on these markets and increases the risk of a larger wave of defaults in the future.

It is not only the scale but the complexity of potential debt restructuring and need for global cooperation that will determine the extent to which defaults can be contained (Figure 2.10). Creditors have expanded to include quasi-sovereign entities and the private sector, such as commodity traders and producers. Although this expansion has provided new avenues of financing, the coordination of relief between international organizations, the “Paris Club” and other state creditors, as well as the private sector will continue to complicate attempts at restructuring. For example, only three countries – Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia – are currently undergoing treatment under the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments. All remain unresolved, reflecting challenging geopolitical and economic dynamics as well as a lack of transparency.131

The call for wealthier economies to intervene bilaterally is growing – likely increasing longer-term geopolitical tensions. China has become a large bilateral creditor to many low-income countries and, by some estimates, has become the largest official creditor globally.132 Energy exporters, such as the Middle East and the United States of America, are also well-placed to step into the gap over the medium-term. Renewed soft power approaches and debt-trap diplomacy could redraw regional and global political lines, driving currency blocs and possibly exacerbating pressures on developing countries as supply chains shift to mirror economic alliances.133 This trend could also destabilize security dynamics, as debt is leveraged to pull developing economies into the military expansion of larger powers (see Chapter 2.4: Human security).

Yet as the number of sovereign defaults grow, creditor countries and companies could become more exposed to debt contagion, including systemically important banks, pension funds and state creditors. This will interact with other domestic debt vulnerabilities, including the private sector and state-owned entities,135 to raise aggregate exposure and place pressure on the solvency of even advanced and large emerging economies. A sovereign debt default in a systemically important economy could result in systemic proliferation with a devastating impact on a global scale.

A looming investment shortfall

Even in the absence of a global crisis, the 1980s “lost decade” of development in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa provides a very real example of the economic and humanitarian crisis that can arise from a sovereign debt default, including currency free falls, collapses in output, cost-of-living crises and rapid increases in poverty. The 41 countries that defaulted on their debt in the first half of the decade required eight years, on average, to reach their pre-crisis GDP per capita.136 Debt distress and restructuring will also have an impact on investment. According to GRPS results, the risk of Debt crises drops in perceived severity over the longer-term time frame, but the Collapse or lack of public infrastructure and services becomes more severe. The ability to finance continued productivity and resilience will be hampered by economic and political dynamics on both a global and national level.

Advanced economies will have more autonomy to invest in future priorities, while developing markets may be more beholden to the demands of the creditor, meaning money could be diverted from the areas of greatest social need, including expenditure in public goods and infrastructure. Beyond the growing financial cost of natural disasters, emerging and developing economies will need to spend a higher proportion of GDP on the green transition and sustainable infrastructure, with knock-on ramifications for other public spending and services.137 By contrast, within the limits of inflationary pressures, advanced economies can continue to leverage more accessible financing for economic development, such as stronger industrial policy, to underpin the energy transition, widening the divide between countries. Necessary fiscal consolidation in emerging and developing economies may also rely heavily on spending cuts, which could rapidly remove social protection available to low-income and vulnerable populations, increasing poverty and inequality within countries, alongside social and political unrest.

Yet in a structurally different, low-growth, low-investment economic era, even advanced economies will need to make trade-offs. Rising unemployment, social unrest and political polarization, and even technologically-driven churn in both blue- and white-collar jobs may influence the prioritization of current expenditure over longer-term capital expenditure, while security considerations may mean there is less fiscal headroom for social and environmental development over the medium term. The potential result is the de-prioritization of investment and slow decay of public infrastructure and services in both developing and advanced markets.138 Around two-fifths of low- and lower-middle-income countries cut expenditure on education by an average of 13.5% since 2020, which, despite a minor rebound, fell again in 2022.139 As referenced in Chapter 2: Human health, the lingering economic, educational and healthcare overhang of the pandemic continues to weaken the capacity of public systems that also face compounding pressure from ageing populations in advanced economies, and rapidly expanding populations in some developing markets. This is a slow-burning risk: impacts are subtle, lagged and cumulative in nature, but can be highly corrosive in overall impact to the strength of human capital and development – a critical mitigant to the impact and likelihood of other global risks.

Acting today

In recognition of the risks posed to broader financial stability, timely and deeper debt write-downs could allow a faster return to developmental progress for vulnerable countries and render a future default less likely. The private sector could be incentivized to participate in debt restructuring through a variety of mechanisms, including issuing of new bonds with stronger legal protections, loss reinstatement commitments and value recovery instruments – with the latter enabling private creditors to gain from upside developments in debtor countries in the future, such as GDP-linked instruments in Costa Rica, Argentina, Greece and Ukraine.140

As a complementary mechanism to more comprehensive debt restructuring, there may be increased deployment of debt-for-development deals (see Chapter 2.2: Natural ecosystems), particularly relating to climate-positive adaptation, to help break the correlation between exposure to climate change and debt vulnerability.141 However, this should not just be limited to environmental concerns. Social bond issuances have already jumped sevenfold, to $148 billion in 2022, targeting healthcare, education and small and medium-sized enterprises.142 While debt swaps may not create fiscal space beyond the specific objective, SDG-linked conditionality may enhance the willingness of creditors to consider debt relief, particularly for countries where other forms of fiscal support, including write-downs and conditional grants, may be less likely.143

Finally, we are unlikely to be able to double down on debt to the same extent to cushion the next crisis. A more proactive approach to countries that are not yet on the verge of debt distress could help mitigate the systemic risk of sovereign debt contagion. Recognition of simultaneous crises – debt, climate impacts and food security – could be integrated into greater flexibility and more concessional forms of financing available to vulnerable markets. With particular respect to the climate agenda, there is a growing expectation that packages will include grants, rather than rely solely on loans that add to overall debt burdens.144 Bilateral and multilateral underwriting of risk could also enable much-needed flows of private capital, while support for longer-term projects that can help crowd-in private capital, such as the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust, is also critical.145