The Global Cooperation Barometer 2026 – Third Edition

Introduction: The evolution of global cooperation

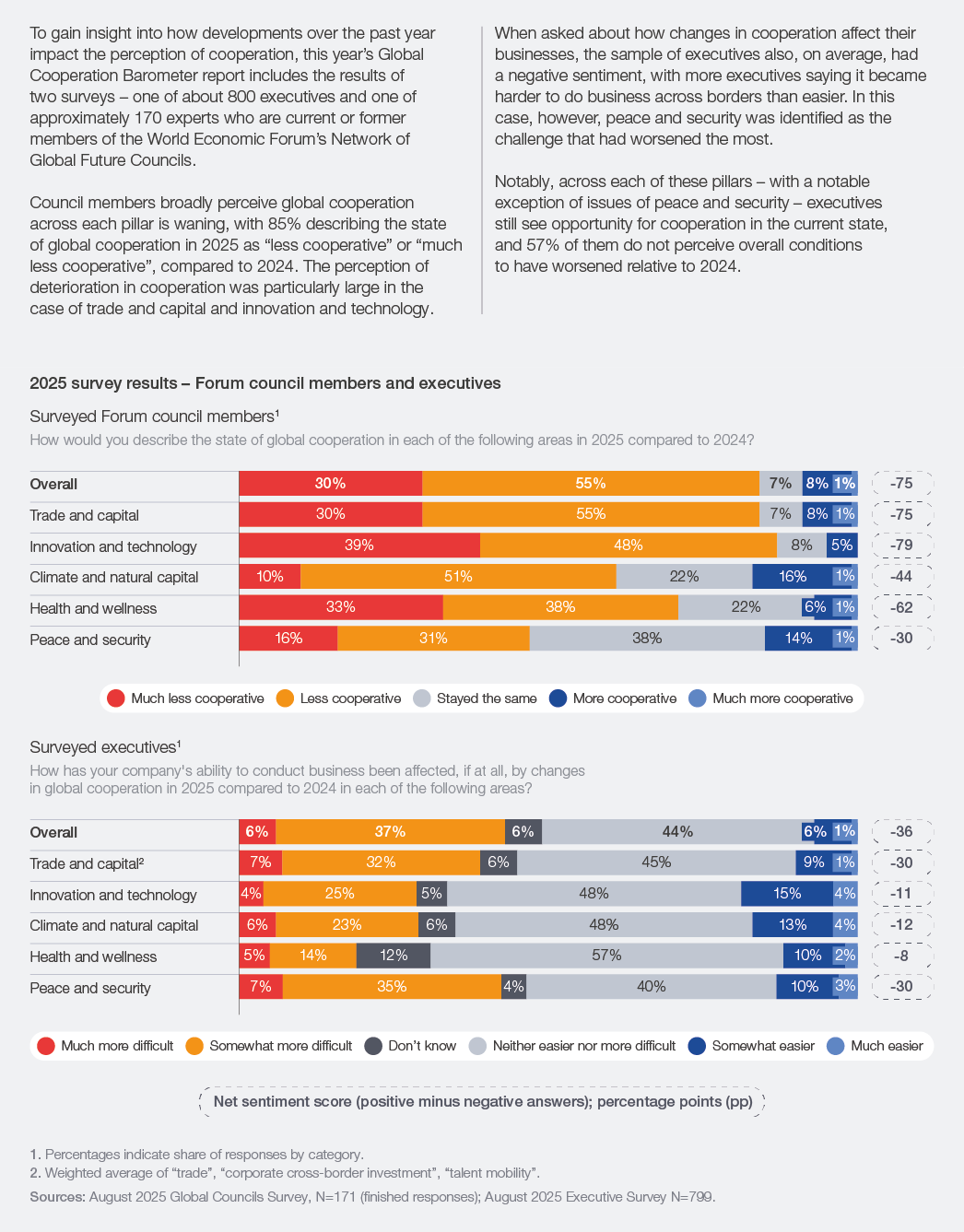

With global multilateral cooperation confronting challenges, smaller and more adaptive cooperative coalitions are emerging.

As a new global era takes shape, multilateralism is under strain, even as global cooperation continues to deliver in some key areas. The world has seen continued fragmentation, as trade barriers have escalated, levels of mistrust have remained high and geopolitical tensions have been an ever-present overhang. Conflicts have intensified across several regions and forced displacement reached record levels.2

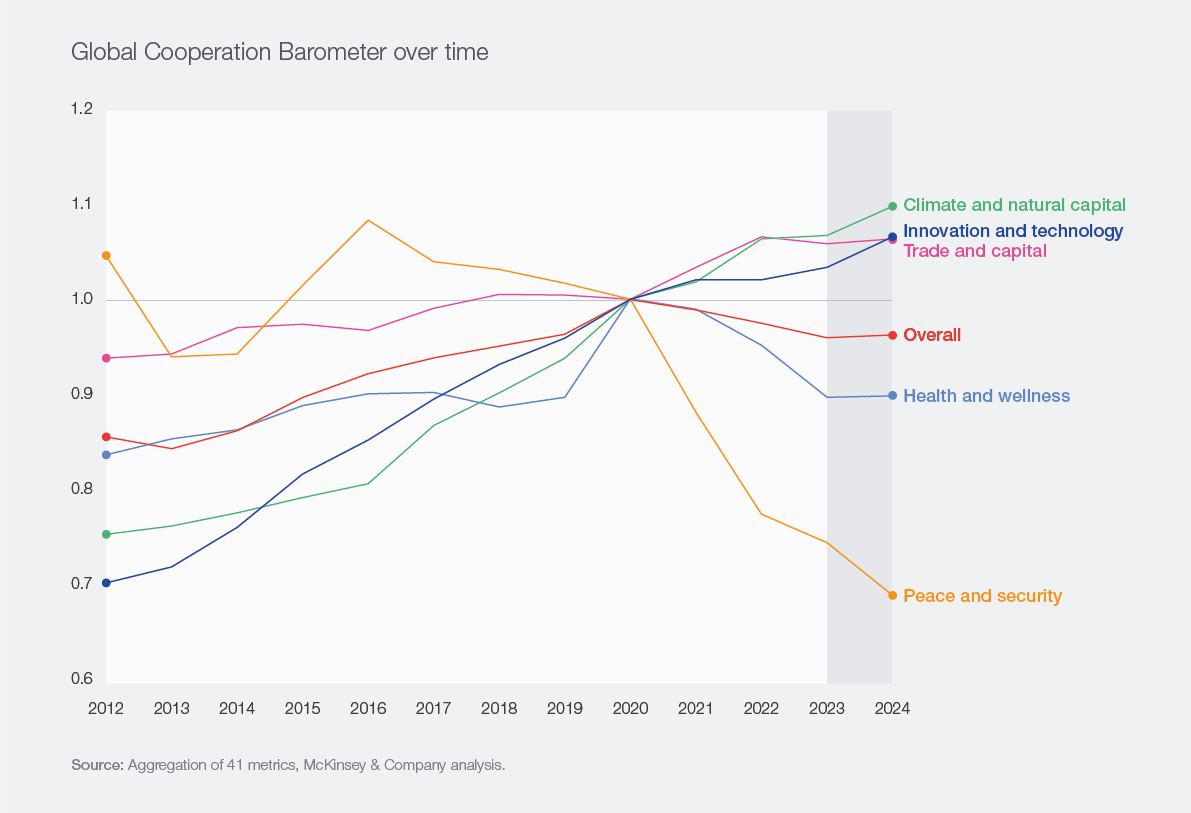

In this sobering context, the Global Cooperation Barometer’s measurement of overall cooperation has held steady (Figure 2). While stress to the global cooperative system may not be surprising, the resilience of overall cooperation may be. Although cooperation tied to global multilateralism (which relies on common goals and actions often advanced through international institutions) has largely declined, cooperation through alternative, often flexible and purpose-built coalitions has continued. Most notably, cooperation among smaller groups of countries has persisted as economies continue to find value in working with each other through pragmatic, agile, interest-based partnerships.3 This dynamic is often dubbed “minilateralism” or sometimes “plurilateralism”.4

The result is that cooperation is far from dead. In tracking 41 individual metrics, the barometer shows how cooperation is adapting to a new context. Most cooperation metrics remain above their 2019 levels, and all pillars except peace and security show strong positive momentum in at least some areas. Evidence signals these trends have persisted through 2025.

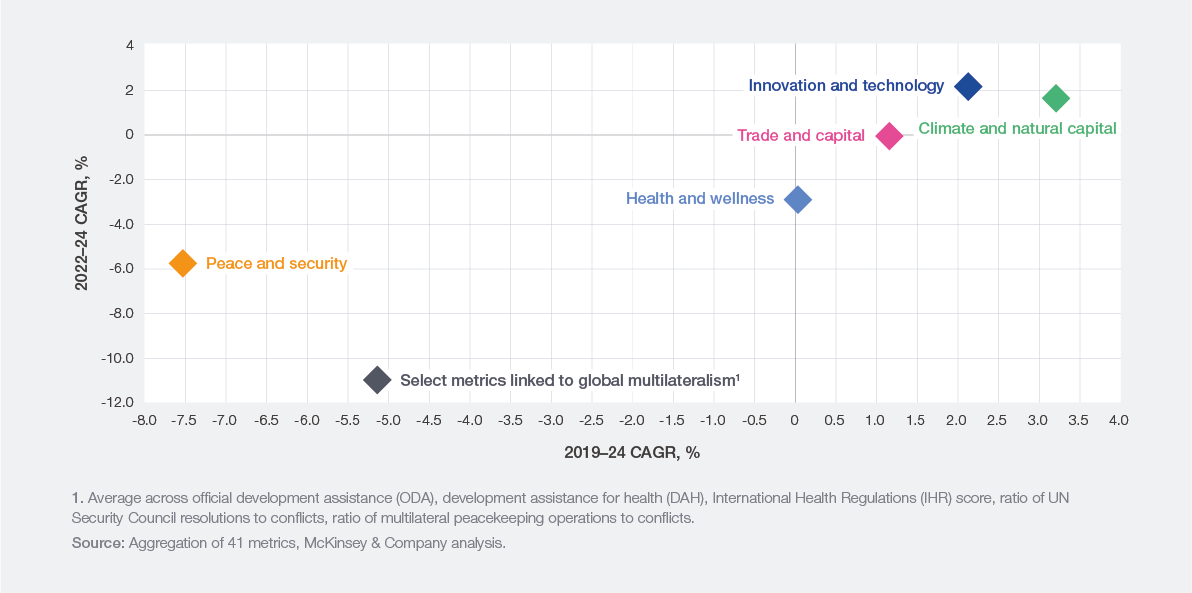

Looking more closely, the barometer shows increasing levels of cooperation for the innovation and technology and climate and natural capital pillars (Figure 3), often in areas where domestic interest or economic incentives are converging with global goals. In the case of innovation and technology, cross-border data flows and digital services fuelled collaboration as countries race to expand their capabilities for a new era of technology-driven economies; while in climate and natural capital, advancements in financing and global trade enabled more clean power and electric transport, especially in places where goals of emissions reduction, increased affordability and increased energy security converged.

The trade and capital pillar shows a flattening of cooperation; while it remains above the 2019 level, with momentum in services and capital flows, goods trade has been hit by protectionist headwinds. Still, it is notable that trade is not meaningfully retreating but rather reconfiguring across different partners. The flattening of cooperation in health and wellness also encompasses distinct dynamics. Most health outcomes stand above pre-COVID-19 pandemic (hereafter referred to as “the pandemic”) levels. However, these outcomes are a function of long-run developments, which could reverse in the future. Pressure on multilateral organizations has eroded development assistance, materially increasing the load on domestic budgets and creating challenges for the future of health in the most vulnerable places.

The peace and security pillar stands out as experiencing the greatest decline, as every metric is below pre-pandemic levels. This pillar exhibits sharp deterioration, as global tensions escalate and multilateral mechanisms are not addressing conflicts.

Figure 2: Global Cooperation Barometer over time

Why cooperation is evolving

Pressure on institutions and arrangements that support global multilateral cooperation has been building for over a decade and a half. The aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis was marked by a long tail of growing dissatisfaction in the globalized international system, with a slowdown in the growth of the shares of trade and cross-border finance in the global economy.5

If the years immediately following the Global Financial Crisis were a period of brewing cooperative malaise, the most recent five years delivered a series of acute shocks that tested the very construct of global multilateralism. The pandemic, the Russia–Ukraine conflict and resulting energy shock, escalating conflict in many regions and more interventionist trade policies all rattled long-held norms and systems underpinning cooperation. These shocks have sharpened debates over how to balance domestic imperatives with shared objectives – from emissions cuts and security to competitiveness and development – and they have prompted the system’s own stewards to call for renewal and reform, including the World Trade Organization (WTO), the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank.6

As these shocks have rippled around the world, they have reshaped, rather than shattered, the contours of cooperation. To be sure, cooperation has receded in many areas (notably, as mentioned, regarding global multilateralism and global security and trade). Yet five years on from the start of the pandemic, a new, nuanced picture of cooperation is starting to emerge – one in which cooperation is adapting to a more multipolar reality, and where economies are still pursuing global objectives, but focusing on where and when they see it as a viable pathway to advance their respective priorities.

The Global Cooperation Barometer reflects the retreat from global multilateralism, as metrics tied to multilateral mechanisms have dropped (Figure 3). For example, by the end of 2024, peacekeeping activity, multilateral resolutions and health aid had all dropped by more than 20% since the pre-pandemic level of 2019, despite the number of conflicts and the need for humanitarian assistance increasing in the same period. In 2024 alone, foreign aid dropped by 11%, a trend that has been exacerbated in 2025.

Figure 3: Evolution by pillar: 2022–24 compound annual growth rate (CAGR) compared to 2019–24 CAGR

As multilateral approaches become more fraught, new, smaller and more agile coalitions – both at the inter- and intra-regional levels – are filling the gaps. In the case of trade, amid increased tensions among the world’s largest economies, smaller, trade-dependent economies are taking greater agency to safeguard the benefits of economic integration. The Future of Investment and Trade (FIT) Partnership, launched in September 2025 and co-convened by New Zealand, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland, brings together 14 economies to pilot practical cooperation. Even in the case of the most sensitive flows of technology and resources, aligned partners are deepening cooperation, such as the US reinforcing ties in critical minerals7 with countries including Australia, Canada and Japan; or artificial intelligence (AI) cooperation among India, the Gulf, Japan and Europe.8

On climate action, the European Union (EU) aims to combine competitiveness with decarbonization through the Net-Zero Industry Act and the Clean Industrial Deal, while implementing the Critical Raw Materials Act to shore up strategic inputs. At the intra-regional level in South-East Asia, the LTMS-PIP (Laos PDR–Thailand–Malaysia– Singapore Power Integration Project) cross-border power-trading scheme is an early step towards an integrated Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Power Grid – bolstering energy security and enabling more clean-power deployment.9

Similarly, on health, several emerging economies are strengthening regional bloc-level access to medicines. Notable 2025 moves include the launch of the African Medicines Agency in October and the Accra Compact on African health sovereignty, as well as the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States scaling a model to reduce the price of insulin throughout the region.10

As a general rule, across all pillars, cooperation is highest where there are clear national interests – often economic – binding countries. This may reflect what UN Secretary-General António Guterres called “hard-headed pragmatism” – the notion that cooperation makes sense when doing so yields meaningful mutual benefit.11

Importantly, while the pressure on global multilateralism has increased, the story is not one of a system in full collapse. In May 2025, World Health Organization (WHO) member states adopted the world’s first Pandemic Agreement after three years of challenging negotiations. On digital cooperation, 65 UN Member States convened in Viet Nam in October 2025 for the signing ceremony of the United Nations Convention against Cybercrime, which will facilitate cooperative approaches to combating cybercrime. On the environment, after two decades of negotiations, the UN High Seas Treaty has reached the required 60 ratifications and will enter into force in January 2026, unlocking the world’s first legally binding framework for protecting two-thirds of the oceans beyond national jurisdiction. While these instances offer an indication that cooperation at the global level has continued even in a more contested landscape, it is notable that the world’s largest economy, the US, is not party to the health and cyber agreements and did not participate in the G20 Summit in South Africa.

The views of experts and executives on cooperation