COVID-19: How to fight disease outbreaks with data

Quicker diagnosis means swifter quarantine, helping to prevent a virus from spreading. Image: REUTERS/Flavio Lo Scalzo

Explore and monitor how COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

COVID-19

- With machine learning we can identify outbreaks and predict their movement.

- Collating relevant data and standardizing it at a global level is complicated.

- Linking clinical and travel data with family history and lifestyle would enable detailed predictions.

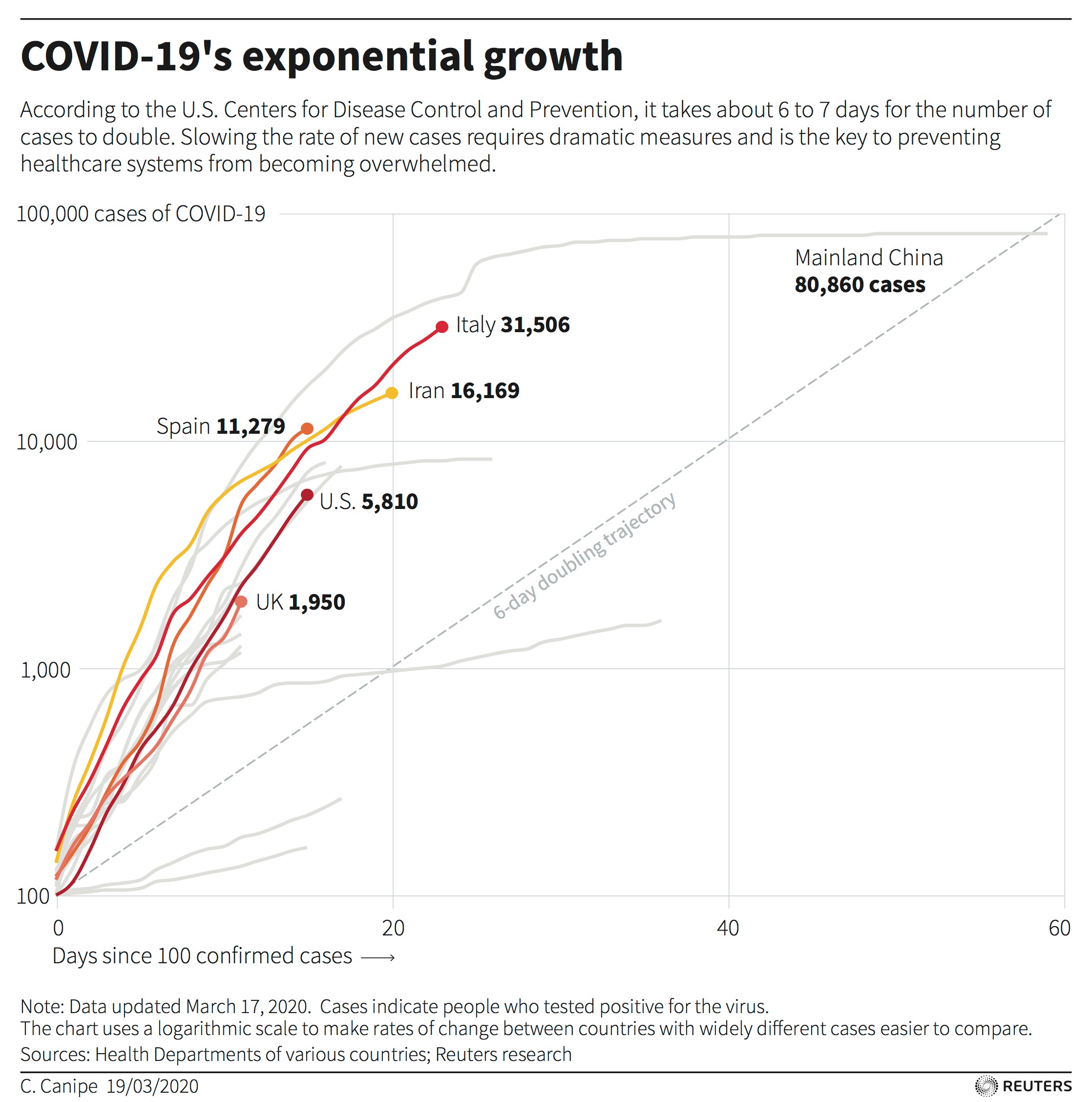

Throughout history, the movement of people has helped disease travel quickly around the world. From the 1918 influenza pandemic which infected 500 million people due to the mass movement of demobilized troops at the end of the First World War, through to modern day viruses like COVID-19, which has spread rapidly due to the accessibility of global travel.

The good news is that in today’s age of information, our global connectivity gives us a strong advantage in fighting infectious disease. We can analyze masses of data across different parts of the world to identify outbreaks and use advanced machine learning models to predict future movement across geographies. The challenge is that collating relevant data and standardizing it at a global level is a complicated task.

One of the keys to collecting good quality healthcare data is quick diagnostics. The private sector continues to deliver innovations that can collate and share diagnostic results almost immediately, helping to monitor the spread of the virus at greater speed and scale.

Companies around the world are investing in developing new testing kits that can test for COVID-19 in just 15 minutes, significantly quicker than the regular nasal swabs that are being used, which can take 24 hours to process. New tests will be able to test passengers with symptoms as they arrive at an airport, before findings are then shared with local health authorities in real time through cloud-enabled connectivity.

At airport immigration counters, biometric authentication offers real-time tracking of populations by integrating facial recognition with thermal imaging. Contactless biometrics systems have the added benefit of reducing contact over shared surfaces or finger scanners.

Quicker diagnosis means swifter quarantine, helping to prevent a virus from spreading through an airport or into a new country. Rapid diagnostics also deliver quicker access to valuable data that could help make pre-emptive containment measures even more effective.

But when it comes to standardizing good quality, health-related data on a global level and extracting relevant insights to policymakers in time, we face two key challenges.

First, collecting the type of data that is most useful for tracking disease. We have seen a stream of reports published on the impact of COVID-19, but much of the data provided lacks granularity.

In addition to mortality rates, we need to better understand the demographics of those that have been affected. The more information we have regarding which age groups and pre-existing conditions are most at risk, the more accurately we can decide where to focus containment efforts or deploy medical supplies.

We also need to identify the type of broader datasets that could help indicate when another virus might spread. This could mean monitoring the health of communities that regularly interact with animals in case another type of coronavirus was to jump from animals to humans; or tracking other indicators such as unusual health patterns, to stop any other new diseases in their tracks.

Second, we need to find ways to standardize different sources of data. Coordinating diagnostic capabilities and information-sharing formats between hospitals and the public sector is not easy, unless the country in question has a centralized patient record system.

Taiwan’s big data approach to healthcare has served it well in this context. The state has been able to link medical records on the national health insurance database with customs and immigration records to identify and test people who had recently travelled from China, sought medical care, or showed signs of severe respiratory illness.

But in many parts of the world, data does not flow easily from hospitals into the public realm, or across borders. Global data standards have yet to be developed and this creates gaps in datasets and delays in how data can be used to shape global health efforts.

One way to improve the speed at which data is standardized could be to encourage better interconnectivity across national data systems through more homogenous data standards.

This would require a great deal of collaboration between various stakeholders and could be challenging to promote across borders. Which country decides which best practice data collection standards to use? And how realistic is it for low-income countries with limited budgets to upgrade their processes to align with those in the developed world?

Another solution is to use artificial intelligence to process the huge amount of data already available online from public health organizations, population databases and transport records. Automated disease surveillance platforms are already enabling us to track and recognize the spread of disease globally through a combination of machine learning and natural language processing and were able to report the spread of COVID-19 faster than the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Cotrol and Prevention (CDC). Other AI models hope to forecast how climate change and human activity may impact our risk of contracting new zoonotic diseases from animals.

Linking clinical and travel data with personal data collected from social media, such as family history and lifestyle habits, would make it possible to deliver even more detailed predictions related to individual risk profiles and healthcare outcomes.

Critics of surveillance technology may be quick to point out the threats to civil liberties that such systems pose. Monitoring the global movement of people and personal health history is a new frontier for machine learning and will be subject to the same regulatory checks that other artificial intelligence platforms have faced.

COVID-19 has clearly demonstrated the economic cost of remaining on the defensive during an infectious disease outbreak and highlighted the importance of investing in identifying the next pandemic before it emerges. Ultimately, this will rely on cross-sector collaboration and the ability to coalesce private sector innovation into policy through cooperation and a steady flow of information.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on COVID-19See all

Charlotte Edmond

January 8, 2024

Charlotte Edmond

October 11, 2023

Douglas Broom

August 8, 2023

Simon Nicholas Williams

May 9, 2023

Philip Clarke, Jack Pollard and Mara Violato

April 17, 2023